United States Navy

As Boothbay Harbor prepares to celebrate the 64th Annual Windjammer Days, this year’s theme proudly honors the past, present, and retired members of the United States Navy who have served our nation with dedication and distinction. Throughout the coming weeks, we will feature a series of profiles highlighting local Navy service members—sharing their stories, experiences, and the lasting impact of their service. These articles are a tribute to the men and women whose commitment to duty reflects the maritime heritage at the heart of Windjammer Days and the deep appreciation of our community.

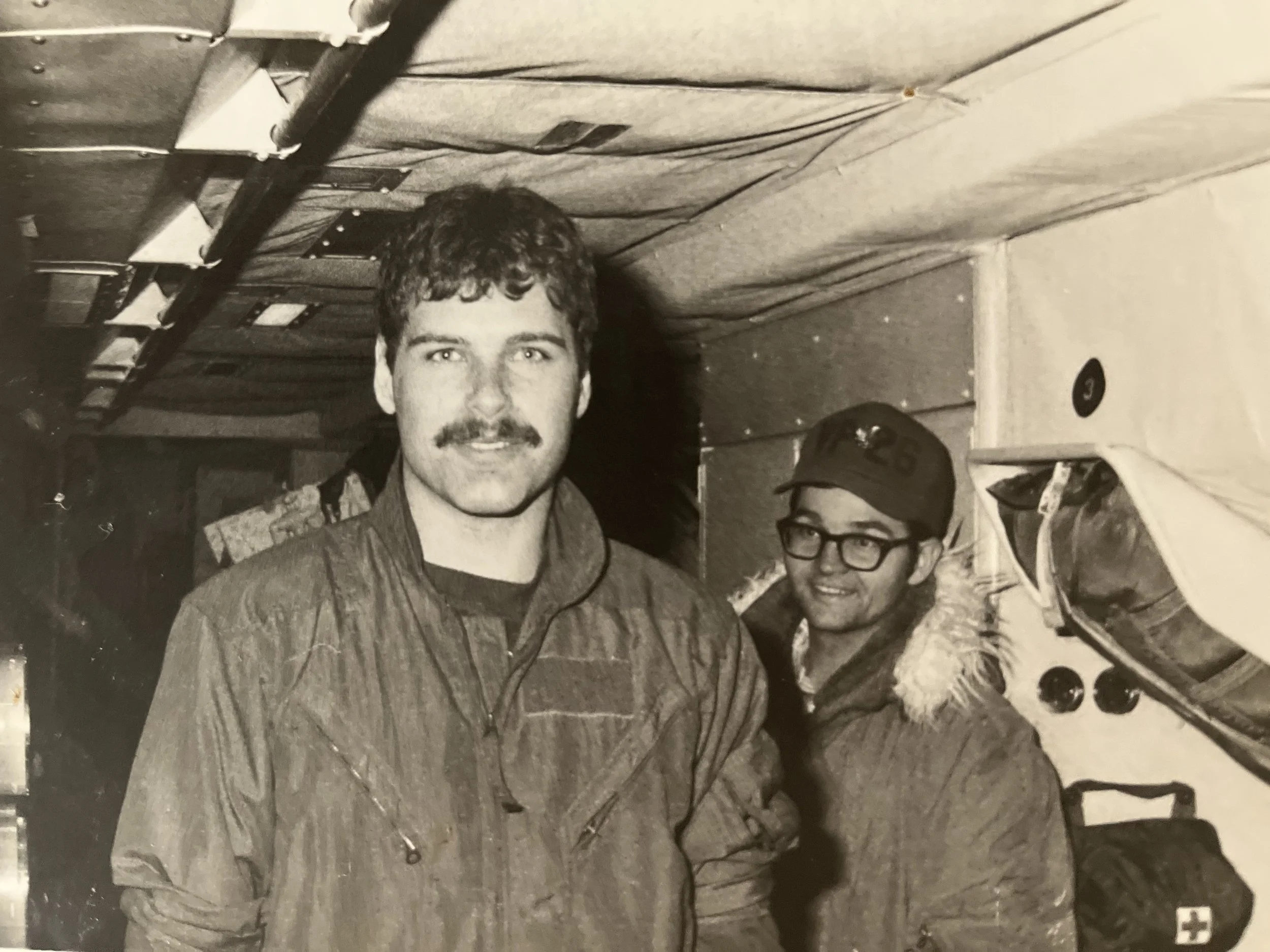

Dr. Barclay M. Shepard Ensign, USNR, United States Maritime Service (Post World War II) and Commander, Medical Corps United States Navy (Vietnam War)

I’ve had the incredible fortune of being at the right place at the right time throughout my 100 years on this earth and some of my greatest memories come from my military experience. I served in the Merchant Marine just after the end of the Second World War aboard an American Export Lines ship from June 1946 thru May 1947, transporting supplies from the United States and to and from various ports in the Mediterranean, Russia, India, Pakistan, and Burma. I sailed aboard the S.S. Coeur d’Alene Victory, one of the many Victory Ships which were built toward the end of World War II to replace the much slower and aging Liberty ships. Each Victory ship was named after a college or university. These were 10,000-ton cargo ships with a horsepower of between 65 and 80 thousand and a speed of between 16 and 18 knots.

I was 3rd Mate aboard ship, and stood the 8-12 watch, morning and night. We crossed the Atlantic many times and on my first voyage I sailed out of New York Harbor. My ship picked up cork, brier (used to make pipes), and pumice from Lipari, which is located north of Sicily in the Aeolian Islands and is where the Stromboli volcano is located. I remember that the water was a beautiful aquamarine color and was very warm so I asked the captain to lower the gangplank so I could go swimming. The water was crystal clear, and I could see the ship’s anchor. Despite the war being over, they were still sweeping mines in the Mediterranean and crews were receiving a moderate hazardous duty pay. At one point, as we approached Trieste, Italy, I saw a mine sweeper explode one of the mines. They had to tow a long line which was carefully set to detonate any mines they encountered.

My second trip was to Odessa, Russia, delivering United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration (UNRRA) goods, which were part of a United Nations relief plan like the United States Marshall Plan for Europe. To reach Odessa, which is located on the north shore of the Black Sea, the ship had to pass through the waterways leading to the Black Sea. The last of these is the Bosphous, which divides the city of Istanbul, Turkey, with Europe to the west and Asia to the east.

It was still early winter, but was unusually cold, and Russian ice breakers had to open a channel so that ships could get to the pier to discharge their cargos. The S.S. Coeur d’Alene Victory tied up next to another cargo ship, the S.S. Mt. Tamalpais. I later found out that the skipper of that ship was the father of a close friend, Dick Banforth, whom I met at Bowdoin College the following year. The cargo we delivered consisted of farm equipment, tractors, and long lengths of large, thin-walled pipe that was designated for a gas line that was to be run from Siberia to Moscow. Curiously, the farm equipment, tractors, and huge coils of heavy manila rope were set aside and soon covered in snow. The only thing the Russians seemed interested in was the pipe.

At the time we were carrying manila rope, which was practically unattainable in the U.S. as almost all supplies of it had gone to the U.S. Navy during the war. After the Russian cargo was unloaded, my ship set out for the trip back to the States. Since the ship was empty with no ballast, the captain took the ship into Oran, North Africa, and 1000 tons of sand ballast was loaded aboard. Shortly thereafter, we hit a hurricane in the mid-Atlantic and it took us six additional days to make port. For me to stay in my bunk, while off watch, I had to tuck one side of my blankets under my mattress!

Finally, we reached Savannah, Georgia, where we unloaded the sand. The ship was brought into a dry dock for inspection. I went underneath the ship and most of the bottom plates had buckled, as the hull was heavily pounded during the storm. Many of these steel plates had to be replaced because they were so badly damaged. There were two holes in two adjacent plates with wires hanging down where the depth finder had once been. I was so impressed by the damage; I took home a small sample piece of the bottom of the ship as a souvenir.

My third voyage was through the Suez Canal, to India, Pakistan, and Burma. While docked in Calcutta, India, I wanted to go into town. This was the period just after the partitioning of India. There were strong tensions between the Muslims and Hindus at that point, as the country was being divided into East and West Pakistan. There was a tremendous shift in the population and many of the Muslims were migrating to Bangladesh or West Pakistan. I clearly remember seeing a huge refugee camp in the City of Madras. The people there were living in sod huts, which had been built one after the other, as far as the eye could see. The refugees with their children were living in squalor, and it was a sad sight that I will never forget.

After leaving the Merchant Mariner service I attended and graduated from Bowdoin College, then followed in my family’s footsteps and pursued a medical degree at Tufts Medical School in Massachusetts. I completed my medical studies, passed my board exams, and became certified as a General Surgeon and later as a Thoracic Surgeon. Duty soon called and in 1967, the Vietnam War was in full swing. I volunteered to serve and was assigned to the U.S.S. Repose AH-16, which was one of two Navy hospital ships serving off the coast of Vietnam. The other was the U.S.S. Sanctuary AH-17. Both ships were based in Da Nang, taking turns steaming up and down the coast of Vietnam during the war.

In October 1967, I flew out to Norton Air Force Base in San Bernardino, California, which is a few miles east of Los Angeles. I then took a charter flight to Da Nang. Navy uniforms are determined by the season, and since my starting point was the northeast coast of the United States in late fall, I wore my dress blues on the plane from Boston. When I finally landed in Vietnam and the airplane door swung open, the oppressive tropical heat hit me all at once, and I realized as I stood on the tarmac that I was probably the only guy in all of Vietnam wearing dress blues!

I remember how confusing Da Nang seemed, and I had to ask a series of people how to get to the hospital ship. No one seemed to know where the Repose was, until finally I asked the right person, and he informed me that a ferry would take me out to the ship and arranged for transportation to the pier. The ferry boat to the hospital ship was actually a World War II landing craft. The Repose was built during the Second World War, and it was originally used as a transport ship, carrying wounded servicemen from the European Theater back home to the United States. It underwent a major reconstruction, and the 10,000-ton, C-2 cargo hull was modified, and turned into a floating hospital with an 850-bed capacity. Many of the bunks were stacked three high throughout the ship.

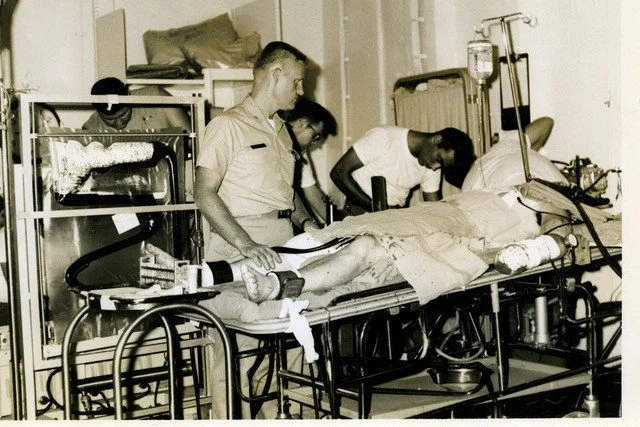

There were three operating rooms aboard the ship, and almost all specialty areas of medicine were covered. There were two general surgeons, two oral surgeons, two neurosurgeons, three orthopedic surgeons, one pediatrician, two internists, one anesthesiologist, a radiologist, a psychiatrist, four general medical officers who had just completed a one-year internship, ten to twelve nurses, a nurse anesthetist, and about 35 corpsmen, some of whom were trained as x-ray and laboratory technicians, and a blood bank. There was also a crew of about 35 officers and enlisted personnel to run the ship. When the Captain, John Drew, found out that I had graduated from Maine Maritime Academy and held a 2nd Mate’s License, he informed me that in addition to my medical duties, I was also qualified to stand watch. I enjoyed the in

Serving aboard the Repose was one of two situations, either quite quiet or extremely chaotic and hectic. There was a helicopter landing pad located on the stern. That is where casualties were brought in from the field. For the first eight or nine months, the casualties were mostly Marine Corps troops, who were serving in the northern part of Vietnam, referred to as I-Corps. As the war progressed, I remember taking care of soldiers who served in the Army, and even a few foreign soldiers from Australia and New Zealand.

The Repose steamed from Da Nang north to the DMZ (demilitarized zone separating North and South Vietnam), often passing the U.S.S. Sanctuary, as the two ships alternated their patrols up and down the coast depending on where they were needed the most. It usually took an average of about 30 minutes or less to bring wounded Marines and Army soldiers from the battlefield to the ship by helicopter. The Army and Navy had Mobile Advanced Medical Aid facilities scattered around Vietnam, but when they were overrun with casualties, they would send the wounded directly from the battlefield to the ship.

It was common for men, who were literally picked up in the field where they lay wounded, to arrive on the ship covered in mud. The Marine Corps helicopters served two missions: To fight in the field and deliver the wounded to the ship. The Army had their own dedicated medivac helicopters called “Dust Offs.” These had a large red cross painted on their nose with the hope that they would not be shot down by the Viet Cong. Sometimes, the wounded arrived at the ship by barge from Da Nang. They were primarily casualties being transferred from the Navy Hospital there. These were the most seriously wounded who required a longer period of care.

The doctors, nurses, and corpsmen aboard the ship were on call 24 hours a day, seven days a week. Imagine trying to operate on a patient when there was a heavy sea running and as the ship rolled from side to side. It wasn’t always easy. Sometimes essential pieces of equipment in the operating rooms had to be lashed down to keep them from rolling around. I remember several times when there was heavy fighting that there was more than one operation going on in the same operating room. I was one of two board certified chest surgeons in the I Corps area of Vietnam at that time. The other served aboard the Sanctuary.

Early in February of 1968 there was a three-day period of the heaviest combat which was called the Tet Offensive. I remember 160 patients being medevacked to the ship in a 24-hour period. We were completely overwhelmed, and I recall that it was crisis after crisis as the crew attempted to tend to the wounded as more and more casualties kept coming. The ship’s triage area was designed to accommodate only ten to 15 patients at a time. This was one of the times when I clearly remember having more than one patient in an operating room at a time. So many men needed major surgical attention. The usual protocol had to be set side, and the surgeons did what they had to do to save the lives of the wounded. The corpsmen were also of great help monitoring the patients who were waiting for surgery. At one point, during the Tet Offensive, the other surgeons and I were up for 36 hours straight, with only short catnaps between cases.

Mail call was a particularly important part of the day aboard ship. I always enjoyed the news from home. I had purchased two, small cassette players and sent one home to my wife in Long Island, New York. In this way, I could send audio messages to her and to my three sons - Douglas, Richard, and David, and they could send messages back to me. One day, my brother, Bob, sailed from our family home in Boothbay Harbor, Maine, down the Sheepscot River, past Southport Island and Pratt’s Island, recording a description of the trip with its beautiful scenery as they went along. He also recorded the melodious sounds of the Cat Ledges gong buoy. Aside from missing my family, I don’t think anything made me feel more homesick than hearing that navigational buoy ringing its three gong bells.

In late October 1968, I completed my one-year tour of service in Vietnam and received orders to return to the states. I remember having mixed feelings about leaving the Repose. On one hand I really missed my wife, sons, and family, but on the other hand I felt very gratified by the work I had been able to perform aboard ship – saving a lot of young men’s lives. I had made a lot of close friends in the year I spent aboard the Repose.

I returned to the states to practice medicine and then I was transferred to the Navy Surgeon General’s Office and spent the next four years heading up the Navy’s Medical Facilities Planning Division in the Bureau of Medicine and Surgery in Washington, D.C. Because of this posting, I had a very interesting assignment the 1970’s. The National War College, which is now called the National Defense University, served to educate both mid-level and military officers and state department officials in geo-political issues. Each year, the entire class was divided into five groups, and they conducted an in-depth study of specific parts of the world. I was assigned to serve as the doctor for a group of about 40 students and was attached to the Far and Middle East group since I had lived there and had a lot of knowledge about that part of the world.

From Turkey we flew to Pakistan where we met President Zulfikar Ali Bhutto. Our next flight was to Tehran the Capital of Iran, and there we met Mohammad Reza Shah Pahlavi, the Shah of Iran, who was very fluent in English. Then it was on to Jeddah, Saudi Arabia where we were ushered into a large square ceremonial hall. There were chairs lined up against the wall to match the exact number of people in our party. We were served tea and coffee. When everyone was served, King Abdulaziz bin Abdul Rahman Al Saud entered the room, and we were asked to stand and form a single file line. Everyone shook hands with the king and then he addressed us in Arabic, which was translated to English. During this trip, I also meet Golda Meir, Israel’s first and only female Prime Minister.

I retired from the Navy in 1978, and joined the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, where I was assigned to the Surgery Department at the VA Central Office in downtown Washington, DC. This was an administrative job that consisted of a three man department. At that time there was a growing issue brewing in the media and among Vietnam Veterans organizations about the possible adverse health effects of exposure to the defoliant Agent Orange.

At one point, I was called to testify before the Senate Veterans Affairs Committee and one of the members on it was a Democratic U.S. Senator from Maine, George Mitchell. At that time, Vietnam Veterans from all over the country had formed their own associations locally, because they were being treated badly when they returned home from war, and wanted to do something to promote change. On this particular day, while testifying, I was asked by Senator Mitchell if I knew of the Vietnam Veterans Association of Maine? To which I replied, “Yes, sir. I’m a native of Maine.” The Senator asked me where I was from and I replied, “Boothbay Harbor.” Without missing a beat and knowing that at the time that the Boothbay Region was a Republican stronghold, the Senator replied into his microphone, “You probably never voted for me.”

During the next five years I was assigned to the department of the VA that was working to create a Computerized Medical Records system for healthcare providers working with veterans. There were five VA medical centers nationwide, that were responsible for working on various aspects of this effort and I was assigned to the one in Washington, D.C.

By 1995, it was time to get busy again, and I accepted the position of Medical Director at the American Hospital in Gaziantep, Turkey. This was the same hospital where my father’s parents, both doctors, had served as medical missionaries from 1882 to 1915, my father, Dr. Lorrin Shepard, was born there and later served as the medical director from 1918 to 1925.

In 2001, I returned to my native town of Boothbay Harbor, where I converted the old summer cottage (Topside) into a year-round house, and I enjoy volunteering for the Community Resource Council and the Woodchucks. In 2025, I fulfilled a life-long dream and self-published my first book in December, A Surgeon’s Slice of Live. A Memoir by Dr. Barclay Shepard, which shows you can do anything if you put your mind to it and is available at Sherman’s Bookstore. My life has gone full circle, and I contribute many of my successes to my time spent in both the Merchant Marine and the U.S. Navy.

William Carroll

What inspired me to join the U.S. Navy was a combination of patriotism, the desire for a true challenge, and the influence of two brothers from my hometown, Jason and Matt Higgins, who had gone before me into the SEAL Teams. Seeing people from our small community accomplish something so demanding showed me what was possible. Their example motivated me to follow in their footsteps and pursue a path that required complete dedication, resilience, and commitment to something greater than myself.

I enlisted after graduating from college, during a time when I was searching for direction and looking for a purpose driven career. I wanted to test myself physically, mentally, and emotionally plus serve in a way that pushed me far beyond my comfort zone. The Navy, and specifically the SEAL community, offered exactly that. Becoming a SEAL is not simply a job; it is a calling that demands every part of who you are.

During my time in the Navy, I served as a Navy SEAL and also specialized as a Joint Terminal Attack Controller (JTAC). My service took me across the Middle East, the Pacific, and Europe, supporting missions alongside teammates who remain some of the finest individuals I’ve ever known. The training and deployments taught me more about discipline, leadership, and teamwork than any classroom ever could.

One experience that stands out in my memory is Hell Week, widely considered one of the most challenging evolutions in military training. It pushes candidates to their absolute limits. The physical exhaustion and mental strain are unlike anything else, but the purpose behind it is clear: real world operations can last for days with little or no rest, and the Teams must know you can endure hardship, stay focused, and support your teammates through anything. Hell Week is not about punishment, it’s about preparation.

My time in the SEAL Teams shaped who I am in every aspect of my life. The team first mindset I learned there guides the way I lead and work with others today. The discipline to keep moving forward, even through failure, is something I carry into my personal and professional life. Integrity and accountability remain core values, and I believe my reputation built through work ethic and character is my most valuable currency.

If I could share one message with young people considering a Navy career, it would be this: it’s about heart. Service teaches perspective, humility, and strength. If you are willing to give everything you have, the Navy can give you a purpose and a foundation that lasts a lifetime.

Above all, I want to honor those we lost, express gratitude for the support I’ve received, and recognize the pride I have in my Maine roots and the values this community gave me.

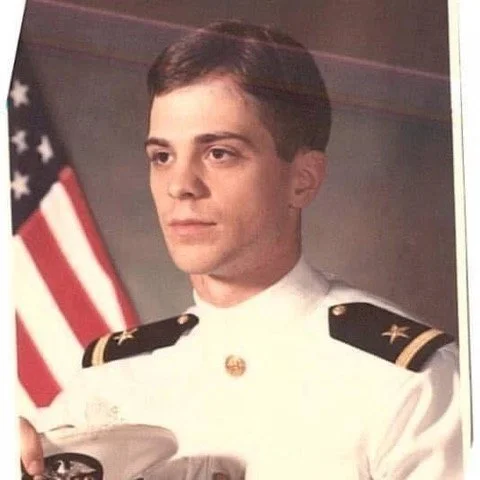

Steve Rosser

I joined the Navy right out of college. I graduated on December 19th 1981 and was in Officer Candidate School (OCS) on January 2nd 1982. Not really having a plan for what I wanted to do, I was enticed by the ads that I read seeking responsibility and a sense of adventure and travel. When I graduated from OCS, I became a Surface Warfare Officer (SWO) with my first job as a Missile Control Officer on a KIDD Class Destroyer USS CALLAGHAN (DDG 994), a ship that is still in active service in the Taiwanese Navy. On my first deployment, we accompanied the Battleship USS New Jersey (BB 62) with port stops all over Asia. I followed that with subsequent tours in Washington DC and onboard the USS CHANCELLORSVILLE (CG 62), an AEGIS Class Cruiser, as the Weapons Officer.

Following my Active Duty time (9 years), I remained in the Naval Reserve for another 15 years, retiring in 2005. I also worked as a contractor in the Defense Industry for another 32 years in a number of jobs supporting Navy and Missile Defense programs, winding up my career as President of a Naval Engineering company supporting critical National Security programs.

All told, I spent over 40 years working in and with the US Navy and Missile Defense Agency (MDA). Because of my association with the Defense Industry, I have travelled the world extensively, working with many Allied Navies including Japan, Spain, and Norway. I can’t imagine how different my life would have been without the Navy. Everything I’ve accomplished and most of my friends tie back to my time in the Navy.

For young people unsure of a job or future after school, serving the Navy or any other service is a great way to serve your country and help determine your future career.

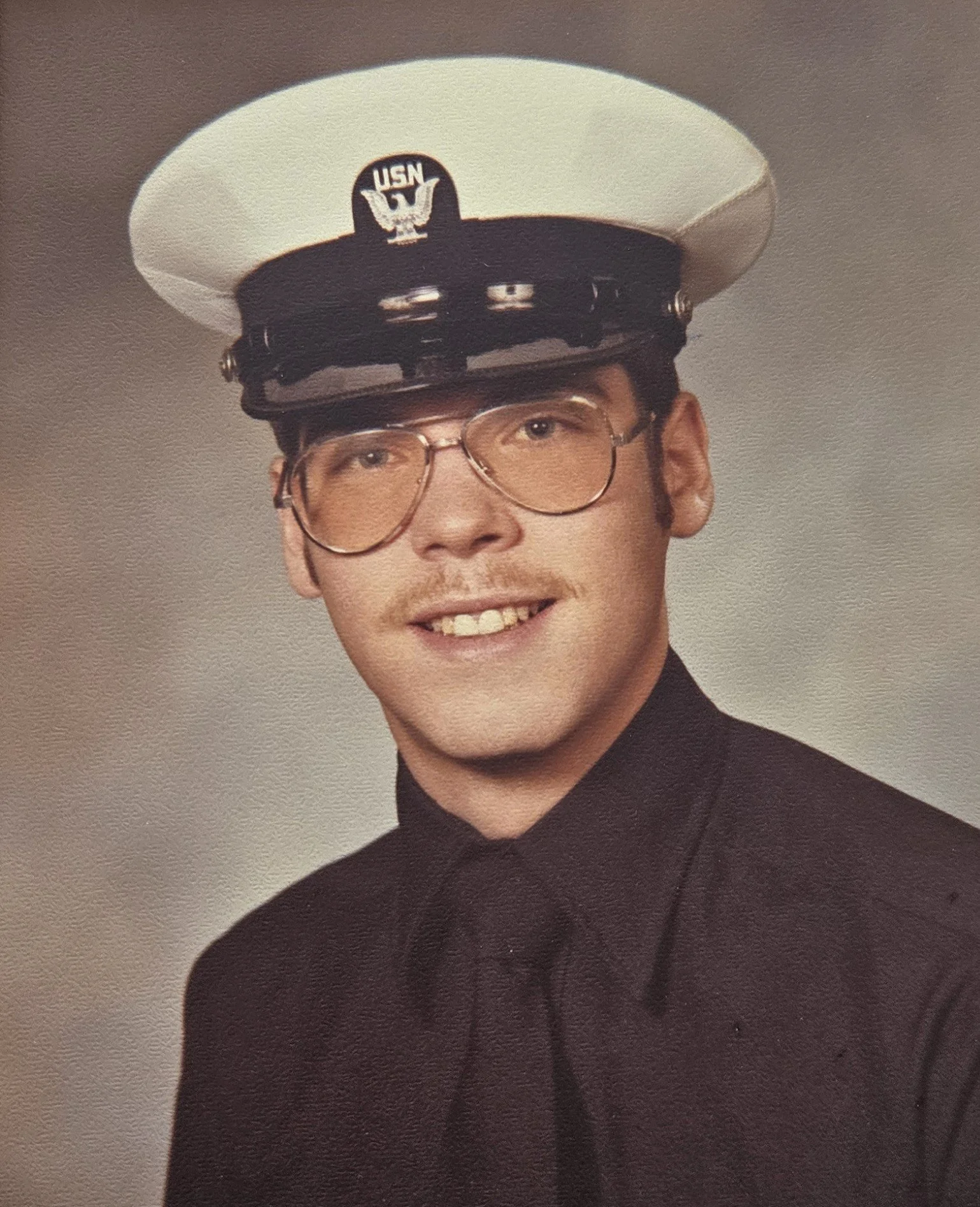

Jay Quinn

After graduating from high school in 1980 I decided if I didn't find a good job by the end of the summer I'd join the Military. I was 18 and working at Zayre’s in Waterville Maine. Like any 18 year old at that time, I partied regularly and had a girlfriend. The reality was that I wasn't going anywhere and it was time to man up and do something useful with my life so I joined the Navy and volunteered for submarines.

I became a Radioman onboard a Ballistic Missile Submarine. Our job was to hide in the North Atlantic waiting for orders to launch missiles. I served from 1980 to 1984 and did three patrols onboard SSBN659 (Will Rodgers) and 1 on SSBN626 (Daniel Webster). A patrol in the 80's typically consisted of a total of 30 days in Holy Loch, Scotland and 60 days out to sea underwater (the longest for me was 72 days underwater). I was honorably discharged as a frocked second class petty officer RM2SS (Submarine Service).

One comical memory is from boot camp. The Seals came in and were trying to get us to sign up. I volunteered figuring if it didn’t work out I'd go back to the Subs. They informed me Submariners are the only ones they couldn't poach, because very few sailors are crazy enough to sign up for Subs, so I was turned down. A more serious memory would be the time a screwup caused our sub to go into a crash dive. We took a down angle sharper than a sub is technically supposed to survive. The sub passed test depth on the way to the bottom which was well below crush depth. Quick thinking by the crew on watch allowed us to surface. The sub was extensively damaged but thankfully no one was injured.

The Navy shaped my character in that it forced me to grow up. Let's face it, when you’re sealed up underwater with 140 other sailors who are depending on you to ensure you'll see the light of day at the end of a patrol, you grow up quick. Don't get me wrong, we raised hell while on land, but got serious when the hatch closed and we dove underwater.

For those considering a career in the Navy, go in with the knowledge that you're giving your country a blank check which could include your life. Too many join thinking it's a game and then whine when it gets tough. It isn't all fun and games, but can be very rewarding.

Submariners are a different breed. We're a bit crazy. We purposely serve on a boat designed to sink. We spend 60+ days over 100 feet underwater and isolated from family and friends. I don't regret any of it. To all who served it doesn't matter if you served 2 or 20 years, only 1% of civilians put on the uniform and risk their lives and all those 1%ers are just as important as the other. Thanks to all of you who put on that uniform to protect us.

Jason Higgins

I joined the United States Navy at 17 years old because of a deep sense of patriotism and a belief that I had from a very

young age: some people are put here to protect others and eliminate bad people from the earth. I always knew I would fight. I always knew I would stand up for what I instinctively knew was right.

My parents played a huge role in that. I watched my father get up every morning at 4 a.m. and come home at 5 p.m., sometimes seven days a week for months at a time. I watched my mother work nonstop as a waitress, sometimes coming home crying after an out of state customer mistreated her. My parents worked tirelessly to raise me and my three siblings, and that work ethic is burned into me. They are my heroes.

I enlisted right after graduating high school. That summer I worked as a lifeguard, running every morning, swimming constantly, and preparing myself physically for what I knew was coming. I enjoyed it. I liked pushing myself.

I was trained in the Navy as an electrician, then went to BUD/S — Basic Underwater Demolition/SEAL training. After passing, I went through advanced training, static line jump school, freefall training, and was assigned to SEAL Team Four in Virginia Beach. My specialty was breaching — opening blocked doors and gates either manually or with explosives.

My service took me all over the world. I deployed multiple times to Panama and Colombia training indigenous forces, which gave me the opportunity to learn jungle warfare, riverine operations, and how to survive off the land. That included swimming in shark-infested waters and experiencing more than one near death situation. I later deployed to the Middle East three times, with stops in multiple other locations.

The day that stands out most was the day I was ambushed — a twelve-hour firefight. We were packing up to head back to Baghdad from another city when troops in the area came under contact. We were the closest unit, so we were called in. As soon as we arrived, we came under heavy automatic weapons fire, sniper fire, and mortar fire. The rounds were snapping by my head and the mortars kept landing closer and closer. We took our first injuries early on.

After six hours we pulled back to reload and were sent right back in. This time we were engaging the enemy as close as ten feet away. At one point I was certain I was going to die, but my only thought was to take as many with me as I could. Later, the fight opened up to distances of 100 to 200 meters and beyond. I spent most of the day on a vehicle-mounted .50 caliber machine gun. My vehicle took over 100 rounds, many of them coming very close to me. I have no idea how I survived other than by the hand of God. I felt it on me that day and many times since.

As the sun went down, five or six Apache helicopters flew overhead, firing missiles simultaneously and wiping out the entire line of enemy combatants. I remember thinking how unbelievable the day was, how alive I felt, and how grateful I was to still be breathing. That night I sat on the roof, smoked a cigarette, looked up at the sky, and felt completely at peace — a deep sense of accomplishment and appreciation for life I have carried with me since.

The Navy turned me from a motivated young man into a highly focused one capable of whatever I set before me. It took the work ethic my parents gave me and taught me how to harness it, rebuild myself, and endure anything. Even after my Navy service and later work supporting national security missions through 2015, that mindset never left me. No matter how hard life gets, no matter what breaks, I will stand tall until God decides my time is over.

When it comes to advice for young people, I tell them this: find something you are deeply passionate about and go all in. Don’t let your own mind talk you out of it. Most people will doubt you, the only opinion that actually matters is your own. Protect it at all costs. I don’t automatically recommend the military. I recommend a peaceful life, living consciously, building a family, and surrounding yourself with love. In the end that’s what life is all about. But if you feel the calling, who am I to dissuade you? I believe that a calling is God-given. Some people are put here for the sole purpose of protecting everyone else. To sacrifice themselves so other may have peace. I was honored to do it during my time.

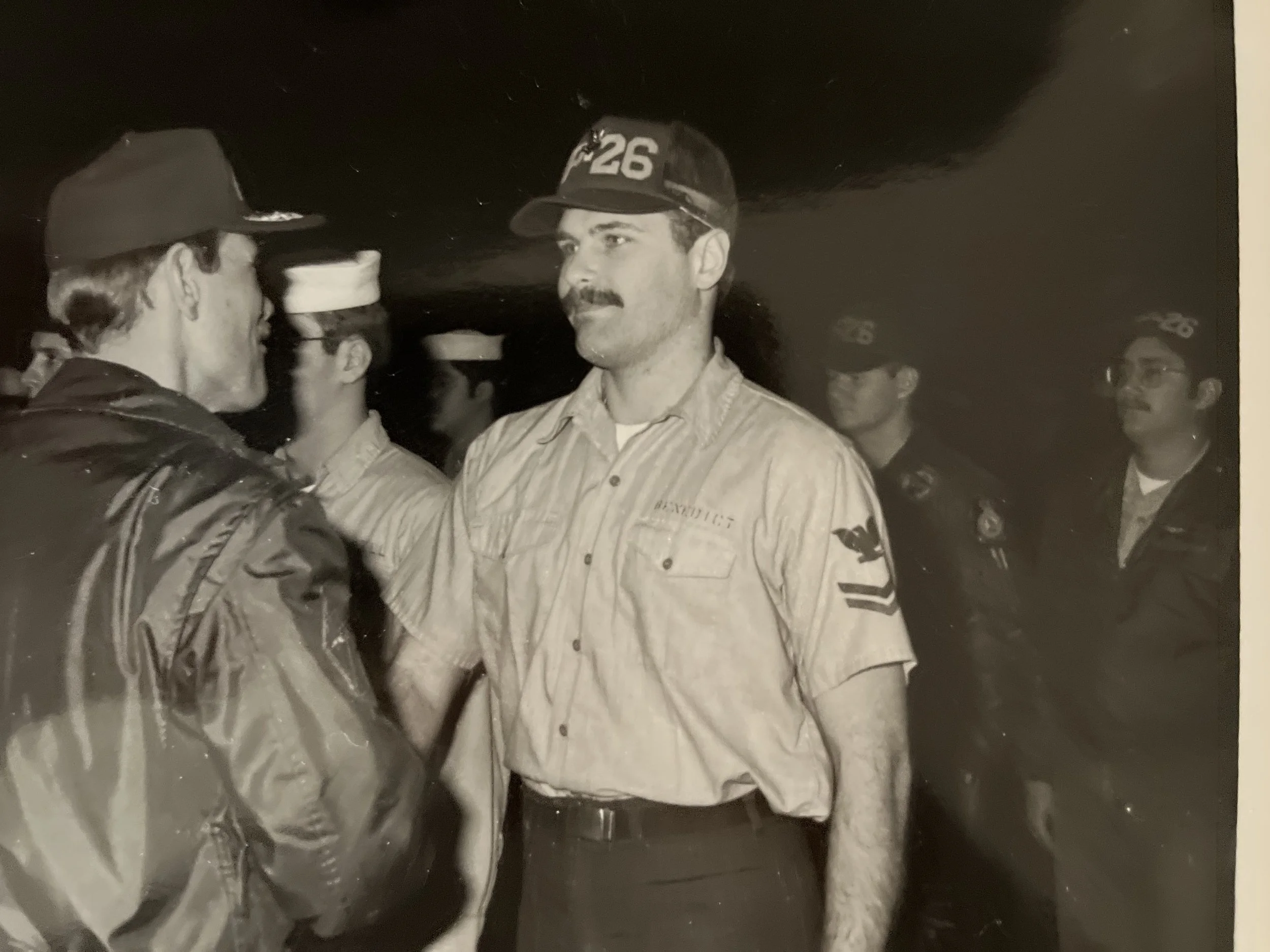

Andy Benedict

I wasn't exactly inspired to join the Navy. I had no idea what I wanted to do with my life and didn't want to spend a lot of money at college to find out.

I enlisted right after high school graduation in 1978 at 18 years old but didn't go to boot camp (in Orlando) until January 1st of 1979. Life was great back then. I actually enjoyed boot camp, for the most part. I was my first time in Florida, and it was nice and warm. It was a big culture shock, as I was coming from a very small town in Pennsylvania to all the diversity of the Navy. I really liked (and still do), the differences in the people from other areas of the country.

I had the best job in the Navy. I was a Photographers Mate and at the time I went to "A" school it was one of the best in the world. The school was in Pensacola, where the Blue Angels train, and we saw them every day. I went from school to Washington D.C., then transferred to NAS Brunswick, VP-26. We deployed to Rota Spain, Keflavik Iceland, and Bermuda. Each deployment was 5 months long. I got to see Scotland, Portugal, and Holland also. I then transferred back to D.C. I finished my Navy time there as an Admiral's photographer and separated in March of 1988 because I wanted to raise my family. My favorite time in the Navy was the 5 months in Spain. I got SCUBA qualified, spent a lot of time at the beach and really enjoyed the culture.

I learned so much from being in the Navy. I learned responsibility, and dependability (qualities that my parents taught me, but were reenforced in the Navy). I met so many interesting people, many of whom showed me a different perspective on the way they thought and acted. The Navy also brought me to Brunswick where I met my wife Lois and we had our two kids right here at St. Andrew’s Hospital.

My advice to anyone who is contemplating joining the armed forces would be: 1) If you want a trade, it is a great place to learn one. 2) If you want to further your education, they will pay a lot of it. 3) If you want to have a career, become an officer. The benefits between officer and enlisted are huge. 4) If you do join, enjoy it.